Difference between revisions of "Factorial"

(add pic and formulas) |

|||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

<div class="thumb tright" style="width:132px; margin:-2px 2px 2px 4px"> |

<div class="thumb tright" style="width:132px; margin:-2px 2px 2px 4px"> |

||

{|class="wikitable" style="margin:0; text-align: right;" cellspacing="0" |

{|class="wikitable" style="margin:0; text-align: right;" cellspacing="0" |

||

| + | ! \(n\) |

||

| − | ! <math>n</math> |

||

| − | ! |

+ | ! \(n!\) |

|- |

|- |

||

| \(-5/2\) || \(4\sqrt{\pi}/3\) |

| \(-5/2\) || \(4\sqrt{\pi}/3\) |

||

| Line 49: | Line 49: | ||

M.Abramowitz and I.Stegun: Handbook of Mathematical Functions. 6. Gamma Function and Related Functions (2010) |

M.Abramowitz and I.Stegun: Handbook of Mathematical Functions. 6. Gamma Function and Related Functions (2010) |

||

</ref> |

</ref> |

||

| − | Frequently, the [[postfix]] notation <math>n!</math> is used for the factorial of number <math>n</math>. |

||

| − | For integer <math>n</math>, the <math>n!</math> gives the number of ways in which ''n'' labelled objects (for example the numbers from 1 to ''n'') can be arranged in order. These are the [[permutation]]s of the set of objects. |

||

| − | In some [[programming language]]s, both n! and factorial(n) , or Factorial(n), are recognized as the factorial of the number <math>n</math>. |

||

| + | Frequently, the [[postfix]] notation \(n!\) is used for the factorial of number \(n\). |

||

| + | For integer \(n\), the \(n!\) gives the number of ways in which ''n'' labelled objects (for example the numbers from 1 to ''n'') can be arranged in order. These are the [[permutation]]s of the set of objects. |

||

| + | |||

| + | In some [[programming language]]s, both n! and factorial(n) , or Factorial(n), are recognized as the factorial of the number \(n\). |

||

==Integer values of the argument== |

==Integer values of the argument== |

||

For integer values of the argument, the factorial can be defined by a [[recurrence relation]]. If ''n'' labelled objects have to be assigned to ''n'' places, then the ''n''-th object can be placed in one of ''n'' places: the remaining ''n''-1 objects then have to be placed in the remaining ''n''-1 places, and this is the same problem for the smaller set. So we have |

For integer values of the argument, the factorial can be defined by a [[recurrence relation]]. If ''n'' labelled objects have to be assigned to ''n'' places, then the ''n''-th object can be placed in one of ''n'' places: the remaining ''n''-1 objects then have to be placed in the remaining ''n''-1 places, and this is the same problem for the smaller set. So we have |

||

| − | : |

+ | :\( n! = n \cdot (n-1)! \,\) |

and it follows that |

and it follows that |

||

| − | : |

+ | :\( n! = n \cdot (n-1) \cdots 2 \cdot 1 , \,\) |

which we could derive directly by noting that the first element can be placed in ''n'' ways, the second in ''n''-1 ways, and so on until the last element can be placed in only one remaining way. |

which we could derive directly by noting that the first element can be placed in ''n'' ways, the second in ''n''-1 ways, and so on until the last element can be placed in only one remaining way. |

||

| Line 69: | Line 70: | ||

The factorial function is found in many combinatorial counting problems. For example, the [[binomial coefficient]]s, which count the number of subsets size ''r'' drawn from a set of ''n'' objects, can be expressed as |

The factorial function is found in many combinatorial counting problems. For example, the [[binomial coefficient]]s, which count the number of subsets size ''r'' drawn from a set of ''n'' objects, can be expressed as |

||

| − | : |

+ | :\(\binom{n}{r} = \frac{n!}{r! (n-r)!} .\) |

The factorial function can be extended to arguments other than positive integers: this gives rise to the [[Gamma function]]. |

The factorial function can be extended to arguments other than positive integers: this gives rise to the [[Gamma function]]. |

||

| Line 77: | Line 78: | ||

===Implicit definition=== |

===Implicit definition=== |

||

| − | The factorial can be defined as unique meromorphic function |

+ | The factorial can be defined as unique meromorphic function \(F\), satisfying |

relations |

relations |

||

| − | : |

+ | :\( F(z+1)=(z+1) F(z) \) |

| − | : |

+ | :\( F(0)=1 \) |

| − | for all complex |

+ | for all complex \(z\) except negative integer values. |

| − | The [[uniqueness]] of function |

+ | The [[uniqueness]] of function \(F\), satisfying these equations, follows from the |

[[Wielandt's theorem]] |

[[Wielandt's theorem]] |

||

<ref name="Wielandt's theorem"> |

<ref name="Wielandt's theorem"> |

||

| Line 94: | Line 95: | ||

===Definition through the integral=== |

===Definition through the integral=== |

||

| − | Usually, the integral representation is used as definition. For |

+ | Usually, the integral representation is used as definition. For \(\Re(z)>-1\), define |

| − | : |

+ | :\( z! = \int_0^\infty t^z \exp(-t) \mathrm{d}t \) |

Such definition is similar to that of the [[Gamma function]], and leads to the relation |

Such definition is similar to that of the [[Gamma function]], and leads to the relation |

||

| − | : |

+ | :\(z!=\Gamma(z+1)\) |

| − | for all complex |

+ | for all complex \(z\) except the negative integer values. |

| − | The definition above agrees with the combinatoric definition for integer values of the argument; at integer |

+ | The definition above agrees with the combinatoric definition for integer values of the argument; at integer \(z\), the integral can be expressed in terms of the elementary functions. |

===Extension of integral definition=== |

===Extension of integral definition=== |

||

| Line 112: | Line 113: | ||

The definition through the integral can be extended to the whole complex plane, using relation |

The definition through the integral can be extended to the whole complex plane, using relation |

||

| − | : |

+ | :\(z!=(z+1)!/(z+1)\) |

| − | for the cases |

+ | for the cases \(\Re(z)<-1\), assuming that \(z\) is not negative integer. |

| − | Also, the symmetry formula takes place for the non-integer values of |

+ | Also, the symmetry formula takes place for the non-integer values of \(z\), |

| − | : |

+ | :\(z! (-z)! =\frac{\pi z}{\sin(\pi z)}\) |

The similar formula of symmetry holds however, for the [[Gamma function]]. |

The similar formula of symmetry holds however, for the [[Gamma function]]. |

||

| − | From this expression, it follows that |

+ | From this expression, it follows that \(\frac{1}{z!(-z)!}\) is [[entire function]] of \(z\). |

| − | Also, this symmetry gives the simple way to express |

+ | Also, this symmetry gives the simple way to express \((1/2)!=\sqrt{\pi}/2\), and, therefore, factorial of half-integer numbers. |

<!-- The f allows to plot the map of factorial in the complex plane. |

<!-- The f allows to plot the map of factorial in the complex plane. |

||

!--> |

!--> |

||

In the figure, |

In the figure, |

||

| − | lines of constant |

+ | lines of constant \(u=\Re(z!)\) and |

| − | lines of constant |

+ | lines of constant \(v=\Im(z!)\) are shown.<br> |

The levels |

The levels |

||

\(u = − 24,\) \(− 20,\) \(− 16,\) \(− 12,\) \(− 8,\) \(− 7,\) \(− 6, \) \(− 5,\) \(− 4,\) \(− 3,\) \(− 2,\) \(− 1,\) \( |

\(u = − 24,\) \(− 20,\) \(− 16,\) \(− 12,\) \(− 8,\) \(− 7,\) \(− 6, \) \(− 5,\) \(− 4,\) \(− 3,\) \(− 2,\) \(− 1,\) \( |

||

| Line 145: | Line 146: | ||

24~\) |

24~\) |

||

are drown with thick blue lines. some of intermediate levels \(v = \mathrm{const}\) are shown with thin green lines.<br> |

are drown with thick blue lines. some of intermediate levels \(v = \mathrm{const}\) are shown with thin green lines.<br> |

||

| − | The dashed blue line shows the level |

+ | The dashed blue line shows the level \(u=\mu_0\) and corresponds to the value \(\mu_0=(x_0)!\approx 0.85\) of the principal local minimum \(x_0\approx 0.45\) of the factorial of the real argument.<br> |

The dashed red line shows the level and corresponds to the similar value of the negative local extremum of the factorial of the real argument.<br> |

The dashed red line shows the level and corresponds to the similar value of the negative local extremum of the factorial of the real argument.<br> |

||

Due to the fast growth of the function, in the right hand side of the figure, the density of the levels exceeds the ability of the plotter to draw them; so, this part is left empty. |

Due to the fast growth of the function, in the right hand side of the figure, the density of the levels exceeds the ability of the plotter to draw them; so, this part is left empty. |

||

| Line 151: | Line 152: | ||

==Factorial of the real argument== |

==Factorial of the real argument== |

||

<div class="thumb tright" style="float:right; margin:-18px 0px 2px 8px; width:360px"> |

<div class="thumb tright" style="float:right; margin:-18px 0px 2px 8px; width:360px"> |

||

| − | {{pic|FactoReal.jpg| |

+ | {{pic|FactoReal.jpg|320px}}<small><center>\(\mathrm{factorial}(x)=x!\); the inverse function, i.e., |

\(\mathrm{factorial}^{-1}(x)\), and \(\mathrm{factorial}(x)^{-1}\) versus real \(x\).</center></small> |

\(\mathrm{factorial}^{-1}(x)\), and \(\mathrm{factorial}(x)^{-1}\) versus real \(x\).</center></small> |

||

</div> |

</div> |

||

| − | The definition above was elaborated for factorial of complex argument. In particular, it can be used to evlauate the factorial of the real argument. In the figure at right, the |

+ | The definition above was elaborated for factorial of complex argument. In particular, it can be used to evlauate the factorial of the real argument. In the figure at right, the \(\mathrm{factorial}(x)=x!\) is plotted versus real \(x\) with red line. The function has simple poluses at negative integer \(x\). |

| − | At |

+ | At \(x\rightarrow -1+o\), the \(x! \rightarrow +\infty\). |

===The local minimum=== |

===The local minimum=== |

||

The factorial has local minimum at |

The factorial has local minimum at |

||

| − | : |

+ | : \(x=\nu_0\approx 0.4616321450\) |

| − | <!--: |

+ | <!--: \(x=\nu_0\approx 0.461632144968362341262659542325721328468196204\)!--> |

marked in the picture with pink vertical line; at this point, the derivative of the factorial is zero: |

marked in the picture with pink vertical line; at this point, the derivative of the factorial is zero: |

||

| − | : |

+ | :\(\mathrm{factorial}^{\prime}(\nu_0)=0\) |

The value of factorial in this point |

The value of factorial in this point |

||

| − | : |

+ | : \(\mu_0=\nu_0!=\mathrm{factorial(\nu_0)}\approx 0.8856031944\) |

| − | <!-- |

+ | <!-- \(\mu_0=\nu_0!=\mathrm{factorial(\nu_0)}\approx 0.88560319441088870027881590058258873320795153367 \)!--> |

| − | The Tailor expansion of |

+ | The Tailor expansion of \(z!\) at the point \(z=\nu_0\) can be writen ax follows: |

| − | : |

+ | :\(z!=\mu_0+\sum_{n=2}^{N-1} c_n (z-\nu_0)^n + \mathcal{O}(z-\nu_0)^N~\) . |

The coefficients of this expansion are copypasted in the table below: |

The coefficients of this expansion are copypasted in the table below: |

||

{|class="wikitable" style="margin:0; text-align: right;" cellspacing="0" |

{|class="wikitable" style="margin:0; text-align: right;" cellspacing="0" |

||

| + | ! \(n\) |

||

| − | ! <math>n</math> |

||

| − | ! approximation of |

+ | ! approximation of \(c_n\) |

|- |

|- |

||

| 2 || 0.428486815855585429730209907810650582960483696962 |

| 2 || 0.428486815855585429730209907810650582960483696962 |

||

| Line 184: | Line 185: | ||

This expansion can be used for the precise evaluation of the inverse function of factorial (arcfactorial) in vicinity of the branchpoint. |

This expansion can be used for the precise evaluation of the inverse function of factorial (arcfactorial) in vicinity of the branchpoint. |

||

| − | Other local extremums are at negative values of the argument; one of them in shown in the figure above. |

+ | Other local extremums are at negative values of the argument; one of them in shown in the figure above. There, it is denoted as \(\nu_1\). |

<!-- |

<!-- |

||

===Specific values=== |

===Specific values=== |

||

For several specific values of the argument, the simple representations for the factorial are known. In addition fo the integer values, |

For several specific values of the argument, the simple representations for the factorial are known. In addition fo the integer values, |

||

| − | + | \(\left(-\frac{1}{2}\right)!=\sqrt{\pi}\); then, using the relation\(z!=z\cdot(z+1)!\), values at half-integer argument can be expressed; for example, \(\left(\frac{1}{2}\right)!=\frac{\sqrt{\pi}}{2}\approx 0.8862269255\) is slightly greater than \(\mu_0\), which is minimal value of this function for the positive values of the argument. |

|

Values of factorial at integer plus quarter and at integer plut third are mentioned in in textbooks, but these numbers do not have special names. |

Values of factorial at integer plus quarter and at integer plut third are mentioned in in textbooks, but these numbers do not have special names. |

||

| Line 195: | Line 196: | ||

==The Taylor expansion== |

==The Taylor expansion== |

||

| − | The [[Taylor expansion]] of |

+ | The [[Taylor expansion]] of \(z!\) at \(z=0\), or the [[MacLaurin expansion]], has the form |

| − | + | \(z!=\sum_{n=0}^{N-1} g_n z^n+\mathcal{O}(z^N)~\) . The first coefficients of this expansion are copypasted in the table below: |

|

<table border="2" cellpadding="4" cellspacing="2" style="margin: 1em 1em 1em 0; background: #ffffff; border: 1px #aaa solid; border-collapse: collapse;"> |

<table border="2" cellpadding="4" cellspacing="2" style="margin: 1em 1em 1em 0; background: #ffffff; border: 1px #aaa solid; border-collapse: collapse;"> |

||

| − | <tr><th> |

+ | <tr><th>\(n\)</th> <th>\(g_n\)</th> <th>approximation of \(g_n\)</th> </tr> |

| − | <tr><td>0</td> <td> |

+ | <tr><td>0</td> <td>\(1\)</td> |

| + | <td>\(\ 1.000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000\)</td> </tr> |

||

| − | <td><math> 1.000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000</math></td> </tr> |

||

| − | <tr><td>1</td><td> |

+ | <tr><td>1</td><td>\(~-\gamma~\)</td> |

| + | <td>\(-0.5772156649015328606065120900824024310421593359399235988\)</td> </tr> |

||

| − | <td><math>-0.577215664901532860606512090082402431042159335939923598805767</math></td> </tr> |

||

| − | <tr><td>2</td> <td |

+ | <tr><td>2</td> <td>\(\frac{\pi^2}{12}+\frac{\gamma^2}{2}\)</td> |

| + | <td>\(\ 0.9890559953279725553953956515006347079391835207282140904\)</td> </tr> |

||

| − | <td><math> 0.989055995327972555395395651500634707939183520728214090443192</math></td> </tr> |

||

| − | <tr><td>3</td><td> |

+ | <tr><td>3</td><td>\(-\frac{\zeta(3)}{3}-\frac{\pi^2\gamma}{12}+\frac{\gamma^3}{6}\)</td> |

| + | <td>\(-0.9074790760808862890165601673562751149286114490725637609\)</td></tr> |

||

| − | <td><math>-0.907479076080886289016560167356275114928611449072563760941328</math></td></tr> |

||

| − | <tr><td>4</td><td |

+ | <tr><td>4</td><td>\(\frac{\pi^4}{160}+\frac{\zeta(3)}{3}-\frac{\pi^2\gamma^2}{12}+\frac{\gamma^4}{24}\)</td> |

| + | <td>\(\ 0.9817280868344001873363802940218508503605736797234654154\)</td></tr> |

||

| − | <td><math> 0.981728086834400187336380294021850850360573679723465415404953</math></td></tr> |

||

</table> |

</table> |

||

| − | Here, |

+ | Here, \(\gamma\) is the [[Euler–Mascheroni constant|Euler constant]] and \(\zeta\) is the [[Riemann function]]. |

The [[Computer algebra system]]s such as [[Maple (sotfware)|Maple]] and [[Mathematica]] can generate many terms of this expansion. |

The [[Computer algebra system]]s such as [[Maple (sotfware)|Maple]] and [[Mathematica]] can generate many terms of this expansion. |

||

| − | The [[radius of convergence]] of the Taylor series is unity, and the coefficient |

+ | The [[radius of convergence]] of the Taylor series is unity, and the coefficient \(g_n\) does not decay as \(n\) increases. However, due to the relation \(z!=z\cdot \mathrm{factorial}(z)\), for any real value of argument of factorial, the expansion above can be used for the precize evaluation of factorial of the real argument, running the approximation above for an argument with modulus not larget than halh. |

Also, the expansion at the half-integer values can be used: |

Also, the expansion at the half-integer values can be used: |

||

| − | + | \(z!=\sum_{n=0}^{N-1} h_n~\left(z-\frac{1}{2}\right)^n+\mathcal{O}\left(\left(z-\frac{1}{2}\right)^N\right)~\) . The first coefficients of this expansion are copypasted in the table below: |

|

<table border="2" cellpadding="4" cellspacing="2" style="margin: 1em 1em 1em 0; background: #ffffff; border: 1px #aaa solid; border-collapse: collapse;"> |

<table border="2" cellpadding="4" cellspacing="2" style="margin: 1em 1em 1em 0; background: #ffffff; border: 1px #aaa solid; border-collapse: collapse;"> |

||

| − | <tr><th> |

+ | <tr><th>\(n\)</th> <th>\(h_n\)</th> <th>approximation of \(g_n\)</th> </tr> |

| − | <tr><td>0</td> <td |

+ | <tr><td>0</td> <td>\(\frac{\sqrt{\pi}}{2}\)</td> |

| + | <td>\( 0.88622692545275801364908374167057259139877472806 \)</td> </tr> |

||

| − | <td><math>0.886226925452758013649083741670572591398774728061193564106905 </math></td> </tr> |

||

| − | <tr><td>1</td><td |

+ | <tr><td>1</td><td>\(\frac{-\sqrt{\pi}}{2}(\gamma+\log(4)-2)\)</td> |

| + | <td>\( 0.03233839744888501382886988426897030778133478887\)</td> </tr> |

||

| − | <td><math>0.0323383974488850138288698842689703077813347888705070206366386</math></td> </tr> |

||

| − | <tr><td>2</td> <td |

+ | <tr><td>2</td> <td>\(\frac{\pi^{5/2}}{8}+\sqrt{\pi}\gamma -\sqrt{\pi}\log(4) +\frac{\gamma^2\sqrt{\pi}}{4} +\sqrt{\pi}\log(2)^2\)</td> |

| + | <td>\( 0.41481345368830116823003762311135634284890996337\)</td> </tr> |

||

| − | <td><math> 0.414813453688301168230037623111356342848909963370422367977736</math></td> </tr> |

||

<tr><td>3</td><td> long expression</td> |

<tr><td>3</td><td> long expression</td> |

||

| + | <td>\(-0.10729480456477221168754195638970966205457592382\)</td></tr> |

||

| − | <td><math>-0.107294804564772211687541956389709662054575923821298300938631</math></td></tr> |

||

<tr><td>4</td><td>even longer expression</td> |

<tr><td>4</td><td>even longer expression</td> |

||

| + | <td>\( 0.14464535904462154303833221025388452407002686153\)</td></tr> |

||

| − | <td><math>0.144645359044621543038332210253884524070026861530981428414028</math></td></tr> |

||

</table> |

</table> |

||

| − | The Taylor series of |

+ | The Taylor series of \(z!\) developed at \(z=1/2\), converges for all \(z\) such that \(|z-1/2|<3/2\). |

| − | In order to boost the approximation of factorial for real values of the argument, and, especially, for the evaluation for complex values, and the evaluation of the inverse function, the expansions for |

+ | In order to boost the approximation of factorial for real values of the argument, and, especially, for the evaluation for complex values, and the evaluation of the inverse function, the expansions for \(\log(z!)\) |

| − | and |

+ | and \(1/z!\) are used instead of the direct Taylor expansions above. |

==Halphing of the imaginary part of the argument== |

==Halphing of the imaginary part of the argument== |

||

| − | While neither |

+ | While neither \(z\) nor \((z+1)/2\) is negative integer, the argument of factorial can be dropped with the identity |

| + | :\( |

||

| − | :<math> |

||

\mathrm{Factorial}(z)~=~\frac{2^z}{\sqrt{\pi}}~ |

\mathrm{Factorial}(z)~=~\frac{2^z}{\sqrt{\pi}}~ |

||

\mathrm{Factorial}\!\left(\frac{z}{2} \right)\cdot |

\mathrm{Factorial}\!\left(\frac{z}{2} \right)\cdot |

||

\mathrm{Factorial}\!\left(\frac{z\!-\!1}{2} \right) |

\mathrm{Factorial}\!\left(\frac{z\!-\!1}{2} \right) |

||

| + | \) |

||

| − | </math> |

||

This may be useful to drop with factor 1/2 the imaginary part of the argument (for example, to apply the Taylor expansion above for the evaluation), but the function has to be evaluated twice. |

This may be useful to drop with factor 1/2 the imaginary part of the argument (for example, to apply the Taylor expansion above for the evaluation), but the function has to be evaluated twice. |

||

==Related functions== |

==Related functions== |

||

<!--{{Image|ArcGamma.jpg|right|400px|ArcFactorial in the complex plane.}}!--> |

<!--{{Image|ArcGamma.jpg|right|400px|ArcFactorial in the complex plane.}}!--> |

||

| − | {{fig|ArcGamma.jpg|360|- |

+ | {{fig|ArcGamma.jpg|360|-38|2|8|ArcFactorial in the complex plane.}} |

In the plot of factorial of the real argument, the two other functions are plotted, |

In the plot of factorial of the real argument, the two other functions are plotted, |

||

| − | + | \(\mathrm{ArcFactorial}(x)=\mathrm{factorial}^{-1}(x)\) and \(\mathrm{factorial}(x)^{-1}\). |

|

These functions are used for the generalization of the factorial and for its evaluation. |

These functions are used for the generalization of the factorial and for its evaluation. |

||

===Inverse function=== |

===Inverse function=== |

||

<div class="thumb tright" style="float:right;"> |

<div class="thumb tright" style="float:right;"> |

||

{|class="wikitable" style="margin:0; text-align: right;" cellspacing="0" |

{|class="wikitable" style="margin:0; text-align: right;" cellspacing="0" |

||

| + | ! \(z\) |

||

| − | ! <math>z</math> |

||

| − | ! ArcFactorial |

+ | ! ArcFactorial\((z)\) |

|- |

|- |

||

<!-- |

<!-- |

||

| 0.88560319441088870027881590058258873320795153367 || 0.461632144968362341262659542325721328468196204 |

| 0.88560319441088870027881590058258873320795153367 || 0.461632144968362341262659542325721328468196204 |

||

|- !--> |

|- !--> |

||

| − | | |

+ | | \(\mu_0\) |

|| 0.46163214496836234126265954233 |

|| 0.46163214496836234126265954233 |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| − | | |

+ | | \(\frac{\sqrt{\pi}}{2}\) |

|| 0.50000000000000000000000000000 |

|| 0.50000000000000000000000000000 |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| Line 280: | Line 281: | ||

Inverse function of factorial can be defined with equation |

Inverse function of factorial can be defined with equation |

||

| − | : |

+ | :\((\mathrm{ArcFactorial}(z))!=z\) |

| − | and condition that [[ArcFactorial]] is [[holomorphic]] in the comlex plane with cut along the part of the real axis, that begins at the minimum value of the factorial of the positive argument, and extends to |

+ | and condition that [[ArcFactorial]] is [[holomorphic]] in the comlex plane with cut along the part of the real axis, that begins at the minimum value of the factorial of the positive argument, and extends to \(-\infty\). This function is shown with |

| − | lines of constant real part |

+ | lines of constant real part \(u=\Re(\mathrm{ArcFactorial}(z))\) and |

| − | lines of constant imaginary part |

+ | lines of constant imaginary part \(v=\Im(\mathrm{ArcFactorial}(z))\). |

Levels \(u=1,2,3\) are shown with thick black curves.<br> |

Levels \(u=1,2,3\) are shown with thick black curves.<br> |

||

| Line 291: | Line 292: | ||

2.2,\) \(2.4,\) \(2.6,\) \(2.8, |

2.2,\) \(2.4,\) \(2.6,\) \(2.8, |

||

3.2,\) \(3.4,\) \(3.6\) are shown with thin blue curves.<br> |

3.2,\) \(3.4,\) \(3.6\) are shown with thin blue curves.<br> |

||

| − | Levels |

+ | Levels \(v=1,2,3\) are shown with thick blue curves.<br> |

| − | Level |

+ | Level \(v=0\) is shown with thick pink line.<br> |

| − | Levels |

+ | Levels \(v=-1,-2,-3\) are shown with thick red curves.<br> |

| − | The intermediate levels of constant |

+ | The intermediate levels of constant \(v\) are shown with thin dark green curves. |

| − | The ArcFactorial has the [[branch point]] |

+ | The ArcFactorial has the [[branch point]] \(\mu_0 \approx 0.85 \); the cut of the range of holomorphizm is shown with black dashed line. |

<!-- The figure shows the mapping ot the [[complex plane]] with the factorial function. |

<!-- The figure shows the mapping ot the [[complex plane]] with the factorial function. |

||

!--> |

!--> |

||

| Line 301: | Line 302: | ||

ArcFactorial for some real values of the argument is approximated in the table at right. |

ArcFactorial for some real values of the argument is approximated in the table at right. |

||

| − | <div class="thumb tright"> |

+ | <div class="thumb tright" style="width:19em;"> |

| − | <div style="width:19em;"> |

||

{|class="wikitable" style="margin:0; text-align: right;" cellspacing="0" |

{|class="wikitable" style="margin:0; text-align: right;" cellspacing="0" |

||

| + | ! \(n\) |

||

| − | ! <math>n</math> |

||

| − | ! approximation for |

+ | ! approximation for \(d_n\) |

|- |

|- |

||

| 1 || 1.43764234228440800 |

| 1 || 1.43764234228440800 |

||

| Line 317: | Line 317: | ||

|} |

|} |

||

</div> |

</div> |

||

| + | In vicinity of the branchpoint \(z=\mu_0\), the ArcFactorial can be expanded as follows: |

||

| − | </div> |

||

| + | :\( |

||

| − | In vicinity of the branchpoint <math>z=\mu_0</math>, the ArcFactorial can be expanded as follows: |

||

| − | :<math> |

||

\mathrm{ArcFactorial}(z)=\nu_0+\sum_{n=1}^{N-1} d_n\cdot \Big(\log(z/\mu_0) \Big)^{n/2} |

\mathrm{ArcFactorial}(z)=\nu_0+\sum_{n=1}^{N-1} d_n\cdot \Big(\log(z/\mu_0) \Big)^{n/2} |

||

| + | \) |

||

| − | </math> |

||

The approximations for the first coefficients of this expansion are copypasted in the table at right. |

The approximations for the first coefficients of this expansion are copypasted in the table at right. |

||

About of 30 terms in this expansion are sufficient to plot the distribution of the real and the imaginary parts of |

About of 30 terms in this expansion are sufficient to plot the distribution of the real and the imaginary parts of |

||

| Line 330: | Line 329: | ||

<!-- In particular, factorial maps the unity to unity; two is mapped to two, and 3 is mapped to 6. !--> |

<!-- In particular, factorial maps the unity to unity; two is mapped to two, and 3 is mapped to 6. !--> |

||

| − | ===Function |

+ | ===Function f(z)=1/z! === |

<div class="thumb tright" style="float:right; margin:2px 0px 4px 8px"> |

<div class="thumb tright" style="float:right; margin:2px 0px 4px 8px"> |

||

| − | {{pic|OneOverFactorial.jpg|400px}}<small><center>\(f(z)=\frac{1}{z!}~\) in the complex |

+ | {{pic|OneOverFactorial.jpg|400px}}<small><center>\(f(z)=\frac{1}{z!}~\) in the complex \(z\)-plane.</center></small> |

</div> |

</div> |

||

The inverse function of factorial, id est, \(\mathrm{ArcFactorial}(z)=\mathrm{Factorial}^{-1}(z)~\) from the previous section, sohuld not be confused with |

The inverse function of factorial, id est, \(\mathrm{ArcFactorial}(z)=\mathrm{Factorial}^{-1}(z)~\) from the previous section, sohuld not be confused with |

||

| Line 340: | Line 339: | ||

\(=\frac{1}{\mathrm{Factorial}(z)}~\), |

\(=\frac{1}{\mathrm{Factorial}(z)}~\), |

||

which is also shown in the figure at right. |

which is also shown in the figure at right. |

||

| − | The lines of constant |

+ | The lines of constant \(u=\Re(f(z))\) and |

| − | the lines of constant |

+ | the lines of constant \(v=\Im(f(z))\) are drawn.<br> |

The levels \(u=-24,\) \(-20,\) \(-16,\) \(-12,\) \(-8,\) \(-7\) \( .. 7,\) \(8,\) \(12,\) \(16,\) \(20,\) \(24\) |

The levels \(u=-24,\) \(-20,\) \(-16,\) \(-12,\) \(-8,\) \(-7\) \( .. 7,\) \(8,\) \(12,\) \(16,\) \(20,\) \(24\) |

||

are shown with thick black lines.<br> |

are shown with thick black lines.<br> |

||

| − | The levels |

+ | The levels \(v=-24,-20,-16,-12,-8,-7 ... 7,-1\) are shown with thick red lines.<br> |

| − | The level |

+ | The level \(v=0\) is shown with thick pink line.<br> |

| − | The levels |

+ | The levels \(v=1,2, ... 7,8,12,16,20,24\) are shown with thick blue lines.<br> |

| − | Some of intermediate elvels |

+ | Some of intermediate elvels \(u=\)const are shown with thin red lines for negative values and thin blue lines for the positive values.<br> |

| − | Some of intermediate elvels |

+ | Some of intermediate elvels \(v=\)const are shown with thin green lines.<br> |

| − | The blue dashed curves represent the level |

+ | The blue dashed curves represent the level \(u=1/\mu_0\) and correspond to the positive local maximum of the inverse function of the real argument.<br> |

| − | The red dashed curves represent the level |

+ | The red dashed curves represent the level \(u=1/\mu_1\), which corresponds to the first negative local maximum of the factorial of the real argument; |

| − | + | \(\mathrm{factorial}^{\prime}(\nu_1)=0\); |

|

| − | + | \(\mathrm{factorial}(\nu_1)=\mu_1\).<br> |

|

In the upper-left hand side of the figure, and at the lower-left hand side of the figure, the density of levels exceeds the ability of the ploter to draw them, and these parts are left empty. |

In the upper-left hand side of the figure, and at the lower-left hand side of the figure, the density of levels exceeds the ability of the ploter to draw them, and these parts are left empty. |

||

| − | + | \(f(z)=\frac{1}{z!}\) is [[entire function]], that grows in the left hand side of the compelx plane and quickly decays to zero along the real axis. |

|

<!-- |

<!-- |

||

===Evaluation of the factorial=== |

===Evaluation of the factorial=== |

||

| − | In principle, the integral representation from the definition above can be used for the evlauation of the factorial. However, such an implementation is not efficient, and is not suitable, when the factorial is used as a component in construction of other functions with complicated representations, involving many evaluations of the factorial. Therefore, the approximations with elementary functions are used. For the efficient evaluation of |

+ | In principle, the integral representation from the definition above can be used for the evlauation of the factorial. However, such an implementation is not efficient, and is not suitable, when the factorial is used as a component in construction of other functions with complicated representations, involving many evaluations of the factorial. Therefore, the approximations with elementary functions are used. For the efficient evaluation of \(z!\), the approximatons for \(1/(z!)\) above, of those for \(\log(z!)\) are used. |

!--> |

!--> |

||

| + | == [[LogFactorial]] == |

||

| − | ===Logfactorial=== |

||

<!--{{Image|LogFactorialZ.jpg|right|400px|LogFactorial at the complex plane.}} !--> |

<!--{{Image|LogFactorialZ.jpg|right|400px|LogFactorial at the complex plane.}} !--> |

||

<div class="thumb tright" style="float:right; margin: 0px 0px 2px 8px"> |

<div class="thumb tright" style="float:right; margin: 0px 0px 2px 8px"> |

||

| Line 370: | Line 369: | ||

For the approximation of factorial, it can be expressed as |

For the approximation of factorial, it can be expressed as |

||

| − | + | \[ z!=\exp(\mathrm{LogFactorial}(z)) |

|

| + | \] |

||

At large values of the argument, the LogFactorial does not show the fast growth and is easier for the numerical implementation, than factorial. |

At large values of the argument, the LogFactorial does not show the fast growth and is easier for the numerical implementation, than factorial. |

||

| + | |||

| − | ====Plof of LogFactorial==== |

||

| + | At real positive values of the argument, [[LogFactorial]] can be interpreted as [[logarithm]] of [[Factorial]]: |

||

| − | Function LogFactorial is shown in figure with lines of constant real part and lines of constant imaginary part. |

||

| + | \[ |

||

| − | Levels of constant <math>u=\Re(\mathrm{LogFactorial}(z))</math> and |

||

| − | + | \mathrm{LogFactorial}(x)=\ln(\mathrm{LogFactorial}(x)), \ x>0 |

|

| + | \] |

||

| + | |||

| + | Function [[LogFactorial]] is shown in figure a right with lines of constant real part and lines of constant imaginary part. |

||

| + | Levels of constant \(u=\Re(\mathrm{LogFactorial}(z))\) and |

||

| + | Levels of constant \(v=\Im(\mathrm{LogFactorial}(z))\) are drawn with solid lines:<br> |

||

Levels \(u=-24,\) \(-20,\) \(-16,\) \(-12,\) \(-8,\) \(-7,\) \(-6,\) \(-5,\) \(-4,\) \(-3,\) \(-2,\) \(-1,\) \(0,\) \(1,\) \(2,\) \(3,\) \(4,\) \(5,\) \(6,\) \(7,\) \(8,\) \(12\) \(,16,\) \(20,\) \(24\) are shown with thick black curves. <br> |

Levels \(u=-24,\) \(-20,\) \(-16,\) \(-12,\) \(-8,\) \(-7,\) \(-6,\) \(-5,\) \(-4,\) \(-3,\) \(-2,\) \(-1,\) \(0,\) \(1,\) \(2,\) \(3,\) \(4,\) \(5,\) \(6,\) \(7,\) \(8,\) \(12\) \(,16,\) \(20,\) \(24\) are shown with thick black curves. <br> |

||

Levels \(u=\) \( |

Levels \(u=\) \( |

||

| Line 388: | Line 393: | ||

3.2,\) \(3.4,\) \(3.6,\) \(3.8\) are shown with thin blue curves.<br> |

3.2,\) \(3.4,\) \(3.6,\) \(3.8\) are shown with thin blue curves.<br> |

||

Levels \(v=-24,\) \(-20,\) \(-16,\) \(-12,\) \(-8,\) \(-7,\) \(-6,\) \(-5,\) \(-4,\) \(-3,\) \(-2,\) \(-1\) are shown with thick red curves.<br> |

Levels \(v=-24,\) \(-20,\) \(-16,\) \(-12,\) \(-8,\) \(-7,\) \(-6,\) \(-5,\) \(-4,\) \(-3,\) \(-2,\) \(-1\) are shown with thick red curves.<br> |

||

| − | Level |

+ | Level \(v=0\) is shown with thick pink line.<br> |

| − | Levels |

+ | Levels \(v=1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,12,16,20,24\) are shown with thick blue lines.<br> |

Levels \(v= |

Levels \(v= |

||

-3.8,\) \(-3.6,\) \(-3.4,\) \(-3.2\) \( |

-3.8,\) \(-3.6,\) \(-3.4,\) \(-3.2\) \( |

||

| Line 403: | Line 408: | ||

Function LogFactorial has singularities at the same points, as the factorial, id est, at negative integer values of the argument. |

Function LogFactorial has singularities at the same points, as the factorial, id est, at negative integer values of the argument. |

||

| + | <!-- |

||

| − | ====Approximation of LogFactorial at large values of the argument==== |

||

| + | ===Approximation of LogFactorial at large values of the argument=== |

||

| + | !--> |

||

<div class="thumb tright"> |

<div class="thumb tright"> |

||

<table border="2" cellpadding="4" cellspacing="2" style="margin: 1em 1em 1em 0; background: #ffffff; border: 1px #aaa solid; border-collapse: collapse;"> |

<table border="2" cellpadding="4" cellspacing="2" style="margin: 1em 1em 1em 0; background: #ffffff; border: 1px #aaa solid; border-collapse: collapse;"> |

||

| − | <tr> <th> |

+ | <tr> <th>\(n\)</th> <th>\(a_n\)</th> <th>approximation of \(a_n\)</th> </tr> |

<tr> <td>0</td> <td> 1 / 12 </td> <td>0.083333333333333333</td> </tr> |

<tr> <td>0</td> <td> 1 / 12 </td> <td>0.083333333333333333</td> </tr> |

||

<tr> <td>1</td> <td> 1 / 30 </td> <td>0.033333333333333333</td> </tr> |

<tr> <td>1</td> <td> 1 / 30 </td> <td>0.033333333333333333</td> </tr> |

||

| Line 413: | Line 420: | ||

</table></div> |

</table></div> |

||

Far from the negative part of the real axis, the function LogFactorial can be approximated through the coninual fraction |

Far from the negative part of the real axis, the function LogFactorial can be approximated through the coninual fraction |

||

| + | \(p\): |

||

| − | <math>p</math>: |

||

| + | \[ |

||

| − | : <math>\mathrm{LogFactorial}(z)= p(z) + \log(2\pi)/2 - z + (z+1/2)~\log(z)</math> |

||

| + | \mathrm{LogFactorial}(z)= p(z) + \log(2\pi)/2 - z + (z+1/2)~\log(z) |

||

| − | : <math>p(z)= \frac{a_0}{z+\frac{a_1}{z+\frac{a_2}{z+\frac{a_3}{z+..}}}}</math> |

||

| + | \] |

||

| − | The coefficients <math>a</math> and their approximate evaluations are copypasted in the table at right. |

||

| + | \[ |

||

| + | p(z)= \frac{a_0}{z+\frac{a_1}{z+\frac{a_2}{z+\frac{a_3}{z+..}}}} |

||

| + | \] |

||

| + | The coefficients \(a\) and their approximate evaluations are copypasted in the table at right. |

||

| − | In vicinity of the real axis, while the modulus of the imaginary part of LogFactorial does not exceed |

+ | In vicinity of the real axis, while the modulus of the imaginary part of LogFactorial does not exceed \(\pi\), the |

LogFactorial can be interpreted as lofarithm of factorial, id est, |

LogFactorial can be interpreted as lofarithm of factorial, id est, |

||

| − | : |

+ | : \(\mathrm{LogFactorial}(z)=\log(z!)\) |

| − | In particular, this relation is valid for positive real values of |

+ | In particular, this relation is valid for positive real values of \(z\). |

| − | For all |

+ | For all \(z\) except negative integers, \( z!=\exp\!\Big(\mathrm{LogFactorial}(z)\Big)\) |

However, the LogFactorial has singularities at negative integer valies of the argument. |

However, the LogFactorial has singularities at negative integer valies of the argument. |

||

| − | == |

+ | ==[[Stirling formula]]== |

| + | |||

Historically, one of the first approximations of the factorial with elementary functions was the [[Stirling formula]] below. |

Historically, one of the first approximations of the factorial with elementary functions was the [[Stirling formula]] below. |

||

| − | For large |

+ | For large \(n\) there is an [[asymptotic]] approximation due to Scottish mathematician [[James Stirling]] |

| + | \[ |

||

| − | :<math> n! \approx \sqrt{2\pi} n^{n+1/2} e^{-n} . \,</math> |

||

| + | n! \approx \sqrt{2\pi} n^{n+1/2} \mathrm e^{-n} |

||

| − | This formula can be obtained from the approximation for LogFactorial above, just replacing <math>p(z)</math> to zero. |

||

| + | \] |

||

| + | This formula can be obtained from the approximation for LogFactorial above, just replacing \(p(z)\) to zero. |

||

| + | With more terms, the [[asymptotic]] \(A\) can be written as flows: |

||

| − | ==Iterated factorial and square root of factorial== |

||

| + | \[ |

||

| − | <div class="thumb tright" style="float:right; margin:0px 0px 2px 8px"> |

||

| + | A(z)= |

||

| − | {{pic|FacitT.jpg|300px}}<small><center>\(y=\mathrm{Factorial}^n(x)\) versus \(x\) for various \(n\)</center></small> |

||

| + | \sqrt{2\pi z}\ \exp\left( |

||

| + | z\log\frac{z}{\mathrm e} + |

||

| + | \frac{1}{12 z} |

||

| + | \left( |

||

| + | 1 |

||

| + | -\frac{1}{30z^2} |

||

| + | +\frac{1}{105z^4} |

||

| + | -\frac{1}{140z^6} |

||

| + | +\frac{1}{99z^8} |

||

| + | -\frac{1}{42z^{10}}<!-- |

||

| + | + O(z^{-12})!--> |

||

| + | \right) |

||

| + | \right) |

||

| + | \] |

||

| + | <div class="thumb tright" style="float:right; margin:-8px 0px 8px 2px; background-color:#fff"> |

||

| + | {{pic|FactoriAsymptoAgreeT.png|270px}}<small><center>Map of agreement \(a(z\!+\!\mathrm i y)\) in the \(x,y\) plane</center></small> |

||

</div> |

</div> |

||

| + | The figure at right shows the map of agreement |

||

| − | Iterated factorial can be constructeed with the |

||

| + | \[ |

||

| − | [[superfunction]] of factiorial and the inverse function, id est, the [[SuperFactorial]] \(F\) and the [[AbelFactorial]] \(G\). The \(n\)th iteration of factorial can be expressed as follows: |

||

| + | a(z) = - \lg \left(\frac{|z!-A(z)|}{|z!|+|A(z)|}\right). |

||

| + | \] |

||

| + | This agreement estimates, how may significant figures can one expect to get with this approximation.<br> |

||

| + | The map or the agreement \(a\) suggests that the approximation \(A(z)\) |

||

| + | provides of order of 14 decimal digits of [[Factorial]]\((z)\) in the range |

||

| + | \[ d = (\ \Re(z) \!\ge\! -6 , \ |z|\!>\!8\ )\ \lor \ (\Re(z)\!<\!-6 , \ |\Im(z)|\!>\!5 \ ) |

||

| + | \] |

||

| + | |||

| + | Function \(A\) is interpreted as [[Restricted asymptotic]]:<br> |

||

| + | It is the [[Sectorial asymptotic]] of [[Factorial]] at large values for sector |

||

| + | \[ |

||

| + | D= \{ z\in \mathbf C \ : |\arg(z)|< \alpha \} |

||

| + | \] |

||

| + | where \(\alpha\) is any positive real number such that \( \alpha < \pi \). |

||

| + | |||

| + | At large \(|z|\), |

||

| + | the residual \(\ r(z)\!=\)[[Factorial]]\((z)\!-\!A(z) \ \) |

||

| + | remains asymptotically negligible compared to [[Factorial]]\((z)\) |

||

| + | in the whole complex \(z\) plane |

||

| + | except an arbitrarily narrow sector containing the negative real axis: |

||

| + | \[ |

||

| + | \lim_{|z|\to \infty, \ z \in D} \frac{r(z)}{z!} = 0 |

||

| + | \] |

||

| + | Here, the limit is not uniform as \(\alpha\to\pi\) . |

||

| + | The mathematically precise version of the formula above can be written as follows: |

||

| + | \[ |

||

| + | \forall \alpha<\pi:\quad |

||

| + | \lim_{|z|\to\infty,\ |\arg z|\le \alpha} |

||

| + | \frac{r(z)}{z!}=0 |

||

| + | \] |

||

| + | |||

| + | In a little bit less efficient form, the asymptotic of [[Factorial]] for large values can be written as follows: |

||

| + | \[ |

||

| + | B(z) = \sqrt{2\pi z} \, \left(\frac{z}{\mathrm e}\right)^z \left(1 +\frac{1}{12z}+\frac{1}{288 z^2} - \frac{139}{51840 z^3} - \frac{571}{2488320 z^4} + \frac{163879}{209018880 z^5} \right) |

||

| + | \] |

||

| + | Function \(B\) also can be interpreted as [[Sectorial asymptotic]] of [[Factorial]], with the same sector \(D\) as for asymptotic \(A\). |

||

| + | |||

| + | ==Iterated factorial and [[square root of factorial]]== |

||

| + | <div class="thumb tright" style="float:right; margin:-8px 0px 2px 2px; background-color:#fff"> |

||

| + | {{pic|FacitT.jpg|300px}}<small><center>\(y=\mathrm{Factorial}^n(x)\) versus \(x\) for various \(n\)</center></small> |

||

| + | </div> |

||

| + | |||

| + | [[Factorial]] is treated as the [[Transfer function]] in book «[[Superfunctions]]» |

||

| + | <ref> |

||

| + | https://www.amazon.co.jp/-/en/Dmitrii-Kouznetsov/dp/6202672862 <br> |

||

| + | https://www.morebooks.de/shop-ui/shop/product/978-620-2-67286-3 <br> |

||

| + | https://mizugadro.mydns.jp/BOOK/468.pdf |

||

| + | D.Kouznetsov. [[Superfunctions]]. [[Lambert Academic Publishing]], 2020. |

||

| + | </ref><ref> |

||

| + | https://mizugadro.mydns.jp/BOOK/202.pdf |

||

| + | Д.Кузнецов. [[Суперфункции]]. [[Lambert Academic Publishing]], 2014. |

||

| + | </ref>. This formalism allows to iterate [[Factorial]] and, in particular, to evaluate |

||

| + | function «[[Square root of factorial]]» \(\varphi\) such that \(\varphi(\varphi(x))=x!\). |

||

| + | |||

| + | The iterates of [[factorial]] are constructed with the |

||

| + | [[superfunction]] of factiorial and the inverse function, id est, the [[SuperFactorial]] \(F\) and the [[AbelFactorial]] \(G=F^{-1}\). The \(n\)th iteration of factorial can be expressed as follows: |

||

\(\mathrm{Factorial}^n(z)= \mathrm{SuperFactorial} \big(n+ \mathrm{AbelFactorial}(z)\big)\) |

\(\mathrm{Factorial}^n(z)= \mathrm{SuperFactorial} \big(n+ \mathrm{AbelFactorial}(z)\big)\) |

||

| Line 456: | Line 542: | ||

In particular, at \(n=1/2\), we have |

In particular, at \(n=1/2\), we have |

||

\({\rm factorial}^{1/2}(z)=\sqrt{\rm factorial}(z)\), where function \(\sqrt{\,!\,}=\sqrt{\rm factorial}\) can be interpreted as [[square root of factorial]]: |

\({\rm factorial}^{1/2}(z)=\sqrt{\rm factorial}(z)\), where function \(\sqrt{\,!\,}=\sqrt{\rm factorial}\) can be interpreted as [[square root of factorial]]: |

||

| − | \(\sqrt{\,!\,}\Big(\sqrt{\,!\,}(z)\Big)=z!\). Name of this function is used as logo of the [[Physics department of the Moscow State University]] and part of logo of [[Main Page|TORI]], |

+ | \(\sqrt{\,!\,}\Big(\sqrt{\,!\,}(z)\Big)=z!\). Name of this function is used as logo of the [[Physics department of the Moscow State University]] and part of logo of [[Main Page|TORI]] in 2009-2014, until the beginning of the [[Russian invasion into Ukraine]]. (Since 2014, all things related to Russia become toxic; so, the logo had been replaced to formulas for the [[Square root of exponential]].) |

| − | Notation \(\sqrt{!} (z)\) happened to be not so convenient |

+ | Notation \(\sqrt{!} (z)\) happened to be not so convenient. The colleagues, who do not know about Logo of the [[Physics Department of the Moscow State University]], confuse |

| − | \(~\sqrt{!} (z)=\sqrt{\mathrm{Factorial}(z) |

+ | \(~\sqrt{!} (z)=\sqrt{\mathrm{Factorial}}(z)~\) with \(~\sqrt{\mathrm{Factorial}(z)}=\sqrt{z!}~\). |

| − | For this reason, |

+ | For this reason, in [[TORI]], notation \(\mathrm{Factorial}^{1/2}(z)\) is used instead. |

==Transfer equation== |

==Transfer equation== |

||

| − | Factorial can be considered as holomorphic solution \(F\) of the transfer equation |

+ | Factorial can be considered as holomorphic solution \(F\) of the generalized transfer equation |

| − | \(F(z\!+\!1)= z \, F(z)\) |

+ | \(F(z\!+\!1)= (z\!+\!1) \, F(z)\) |

| − | However, \(F=\mathrm{Factorial}\) is not only solution of this equation. Name [[Hadmard finction]] is suggested for one of other solutions |

+ | However, \(F=\mathrm{Factorial}\) is not only solution of this equation. Name [[Hadmard finction]] is suggested for one of the other solutions |

<ref> |

<ref> |

||

http://www.luschny.de/math/factorial/hadamard/HadamardsGammaFunction.html |

http://www.luschny.de/math/factorial/hadamard/HadamardsGammaFunction.html |

||

| Line 481: | Line 567: | ||

</i> |

</i> |

||

</ref>. |

</ref>. |

||

| − | |||

==References== |

==References== |

||

| + | {{ref}} |

||

| − | <references/> |

||

http://en.citizendium.org/wiki?title=Factorial |

http://en.citizendium.org/wiki?title=Factorial |

||

| Line 503: | Line 588: | ||

[[Moscow University Physics Bulletin]], 2010, v.65, No.1, p.6-12. |

[[Moscow University Physics Bulletin]], 2010, v.65, No.1, p.6-12. |

||

| + | {{fer}} |

||

| + | ==Keywords== |

||

| + | |||

| + | «[[Amos]]», |

||

| + | «[[ArcFactorial]]», |

||

| + | «[[Arcfactorial]]», |

||

| + | «[[Arcsuperfac.cin]]», |

||

| + | «[[Asymptotic]]», |

||

| + | «[[AuFac.cin]]», |

||

| + | «[[AuFac]]», |

||

| + | «[[Binomial coefficient]]», |

||

| + | «[[Fac.cin]]», |

||

| + | «[[Facp.cin]]», |

||

| + | «[[Factorial]]», |

||

| + | «[[Lof]]», |

||

| + | «[[LogFactorial]]», |

||

| + | «[[Restricted asymptotic]]», |

||

| + | «[[Sectorial asymptotic]]», |

||

| + | «[[Student Distribution]]», |

||

| + | «[[Square root of factorial]]», |

||

| + | «[[SuperFactorial]]», |

||

| + | «[[Superfactorial]]», |

||

| + | «[[SuFac.cin]]», |

||

| + | «[[SuFac]]», |

||

| + | |||

| + | [[Факториал]] |

||

| + | |||

| + | <!-- |

||

[[Category:Articles from CZ]] |

[[Category:Articles from CZ]] |

||

| + | !--> |

||

| − | [[Category:Articles in English]] |

||

| + | [[Category:English]] |

||

[[Category:Factorial]] |

[[Category:Factorial]] |

||

[[Category:Mathematics]] |

[[Category:Mathematics]] |

||

Revision as of 14:53, 19 January 2026

| \(n\) | \(n!\) |

|---|---|

| \(-5/2\) | \(4\sqrt{\pi}/3\) |

| \(-2\) | \(\infty\) |

| \(-3/2\) | -2\(\sqrt{\pi}\) |

| \(-1\) | \(\infty\) |

| \(-1/2\) | \(\sqrt{\pi}\) |

| 0 | 1 |

| 1/2 | \(\sqrt{\pi}/2\) |

| 1 | 1 |

| 3/2 | \(3 \sqrt{\pi}/4\) |

| 2 | 2 |

| 5/2 | \(15 \sqrt{\pi}/8\) |

| 3 | 6 |

| 4 | 24 |

| 5 | 120 |

| 6 | 720 |

| 7 | 5040 |

| 8 | 40320 |

| 9 | 362880 |

| 10 | 3628800 |

In mathematics, Factorial is meromorphic function with fast growth along the real axis; for non-negative integer values of the argument, this function has integer values. [1]

Frequently, the postfix notation \(n!\) is used for the factorial of number \(n\). For integer \(n\), the \(n!\) gives the number of ways in which n labelled objects (for example the numbers from 1 to n) can be arranged in order. These are the permutations of the set of objects.

In some programming languages, both n! and factorial(n) , or Factorial(n), are recognized as the factorial of the number \(n\).

Integer values of the argument

For integer values of the argument, the factorial can be defined by a recurrence relation. If n labelled objects have to be assigned to n places, then the n-th object can be placed in one of n places: the remaining n-1 objects then have to be placed in the remaining n-1 places, and this is the same problem for the smaller set. So we have

- \( n! = n \cdot (n-1)! \,\)

and it follows that

- \( n! = n \cdot (n-1) \cdots 2 \cdot 1 , \,\)

which we could derive directly by noting that the first element can be placed in n ways, the second in n-1 ways, and so on until the last element can be placed in only one remaining way.

Since zero objects can be arranged in just one way ("do nothing") it is conventional to put 0! = 1.

The factorial function is found in many combinatorial counting problems. For example, the binomial coefficients, which count the number of subsets size r drawn from a set of n objects, can be expressed as

- \(\binom{n}{r} = \frac{n!}{r! (n-r)!} .\)

The factorial function can be extended to arguments other than positive integers: this gives rise to the Gamma function.

Definitions

For complex values of the argument, the combinatoric definition above should be extended.

Implicit definition

The factorial can be defined as unique meromorphic function \(F\), satisfying relations

- \( F(z+1)=(z+1) F(z) \)

- \( F(0)=1 \)

for all complex \(z\) except negative integer values. The uniqueness of function \(F\), satisfying these equations, follows from the Wielandt's theorem [2][3]. Historically, the deduction refers to the Gamma function, but the application to the factorial is straightforward.

Definition through the integral

Usually, the integral representation is used as definition. For \(\Re(z)>-1\), define

- \( z! = \int_0^\infty t^z \exp(-t) \mathrm{d}t \)

Such definition is similar to that of the Gamma function, and leads to the relation

- \(z!=\Gamma(z+1)\)

for all complex \(z\) except the negative integer values.

The definition above agrees with the combinatoric definition for integer values of the argument; at integer \(z\), the integral can be expressed in terms of the elementary functions.

Extension of integral definition

The definition through the integral can be extended to the whole complex plane, using relation

- \(z!=(z+1)!/(z+1)\)

for the cases \(\Re(z)<-1\), assuming that \(z\) is not negative integer. Also, the symmetry formula takes place for the non-integer values of \(z\),

- \(z! (-z)! =\frac{\pi z}{\sin(\pi z)}\)

The similar formula of symmetry holds however, for the Gamma function. From this expression, it follows that \(\frac{1}{z!(-z)!}\) is entire function of \(z\). Also, this symmetry gives the simple way to express \((1/2)!=\sqrt{\pi}/2\), and, therefore, factorial of half-integer numbers.

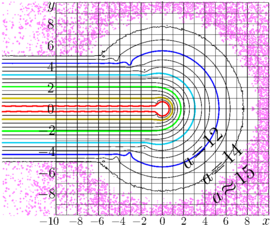

In the figure,

lines of constant \(u=\Re(z!)\) and

lines of constant \(v=\Im(z!)\) are shown.

The levels

\(u = − 24,\) \(− 20,\) \(− 16,\) \(− 12,\) \(− 8,\) \(− 7,\) \(− 6, \) \(− 5,\) \(− 4,\) \(− 3,\) \(− 2,\) \(− 1,\) \(

0,\) \(1,\) \(2,\) \(3,\) \(4,\) \(5,\) \(6,\) \(7,\) \(8,\) \(12,\) \(16,\) \(20,\) \(24\) are drown with thick black lines.

Some of intermediate levels u = const are shown with thin blue lines for positive values and with thin red lines for negative values.

Levels \(v = − 24,\) \(− 20,\) \(− 16,\) \(− 12,\) \(− 8,\) \( − 7,\) \( − 6,\) \( − 5,\) \( − 4,\) \( − 3,\) \( − 2,\) \( − 1\) are shown with thick red lines.

Level \(v = 0\) is shown with thick pink lines.

Levels \(v = 1,\) \(

2,\) \(

3,\) \(

4,\) \(

5,\) \(

6,\) \(

7,\) \(

8,\) \(

12,\) \(

16,\) \(

20,\) \(

24~\)

are drown with thick blue lines. some of intermediate levels \(v = \mathrm{const}\) are shown with thin green lines.

The dashed blue line shows the level \(u=\mu_0\) and corresponds to the value \(\mu_0=(x_0)!\approx 0.85\) of the principal local minimum \(x_0\approx 0.45\) of the factorial of the real argument.

The dashed red line shows the level and corresponds to the similar value of the negative local extremum of the factorial of the real argument.

Due to the fast growth of the function, in the right hand side of the figure, the density of the levels exceeds the ability of the plotter to draw them; so, this part is left empty.

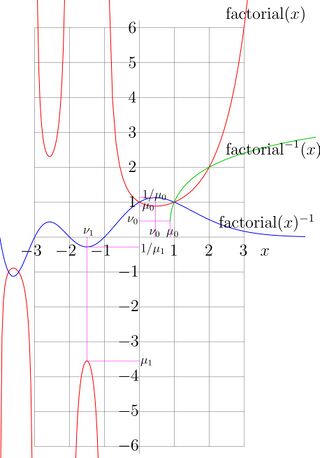

Factorial of the real argument

The definition above was elaborated for factorial of complex argument. In particular, it can be used to evlauate the factorial of the real argument. In the figure at right, the \(\mathrm{factorial}(x)=x!\) is plotted versus real \(x\) with red line. The function has simple poluses at negative integer \(x\).

At \(x\rightarrow -1+o\), the \(x! \rightarrow +\infty\).

The local minimum

The factorial has local minimum at

- \(x=\nu_0\approx 0.4616321450\)

marked in the picture with pink vertical line; at this point, the derivative of the factorial is zero:

- \(\mathrm{factorial}^{\prime}(\nu_0)=0\)

The value of factorial in this point

- \(\mu_0=\nu_0!=\mathrm{factorial(\nu_0)}\approx 0.8856031944\)

The Tailor expansion of \(z!\) at the point \(z=\nu_0\) can be writen ax follows:

- \(z!=\mu_0+\sum_{n=2}^{N-1} c_n (z-\nu_0)^n + \mathcal{O}(z-\nu_0)^N~\) .

The coefficients of this expansion are copypasted in the table below:

| \(n\) | approximation of \(c_n\) |

|---|---|

| 2 | 0.428486815855585429730209907810650582960483696962 |

| 3 | -0.130704158939785761928008749242671025181542078103 |

| 4 | 0.160890753325112844190519489594363387594505844657 |

| 5 | -0.092277030213334350126864106458600575084335085690 |

This expansion can be used for the precise evaluation of the inverse function of factorial (arcfactorial) in vicinity of the branchpoint.

Other local extremums are at negative values of the argument; one of them in shown in the figure above. There, it is denoted as \(\nu_1\).

The Taylor expansion

The Taylor expansion of \(z!\) at \(z=0\), or the MacLaurin expansion, has the form \(z!=\sum_{n=0}^{N-1} g_n z^n+\mathcal{O}(z^N)~\) . The first coefficients of this expansion are copypasted in the table below:

| \(n\) | \(g_n\) | approximation of \(g_n\) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | \(1\) | \(\ 1.000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000\) |

| 1 | \(~-\gamma~\) | \(-0.5772156649015328606065120900824024310421593359399235988\) |

| 2 | \(\frac{\pi^2}{12}+\frac{\gamma^2}{2}\) | \(\ 0.9890559953279725553953956515006347079391835207282140904\) |

| 3 | \(-\frac{\zeta(3)}{3}-\frac{\pi^2\gamma}{12}+\frac{\gamma^3}{6}\) | \(-0.9074790760808862890165601673562751149286114490725637609\) |

| 4 | \(\frac{\pi^4}{160}+\frac{\zeta(3)}{3}-\frac{\pi^2\gamma^2}{12}+\frac{\gamma^4}{24}\) | \(\ 0.9817280868344001873363802940218508503605736797234654154\) |

Here, \(\gamma\) is the Euler constant and \(\zeta\) is the Riemann function. The Computer algebra systems such as Maple and Mathematica can generate many terms of this expansion. The radius of convergence of the Taylor series is unity, and the coefficient \(g_n\) does not decay as \(n\) increases. However, due to the relation \(z!=z\cdot \mathrm{factorial}(z)\), for any real value of argument of factorial, the expansion above can be used for the precize evaluation of factorial of the real argument, running the approximation above for an argument with modulus not larget than halh. Also, the expansion at the half-integer values can be used: \(z!=\sum_{n=0}^{N-1} h_n~\left(z-\frac{1}{2}\right)^n+\mathcal{O}\left(\left(z-\frac{1}{2}\right)^N\right)~\) . The first coefficients of this expansion are copypasted in the table below:

| \(n\) | \(h_n\) | approximation of \(g_n\) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | \(\frac{\sqrt{\pi}}{2}\) | \( 0.88622692545275801364908374167057259139877472806 \) |

| 1 | \(\frac{-\sqrt{\pi}}{2}(\gamma+\log(4)-2)\) | \( 0.03233839744888501382886988426897030778133478887\) |

| 2 | \(\frac{\pi^{5/2}}{8}+\sqrt{\pi}\gamma -\sqrt{\pi}\log(4) +\frac{\gamma^2\sqrt{\pi}}{4} +\sqrt{\pi}\log(2)^2\) | \( 0.41481345368830116823003762311135634284890996337\) |

| 3 | long expression | \(-0.10729480456477221168754195638970966205457592382\) |

| 4 | even longer expression | \( 0.14464535904462154303833221025388452407002686153\) |

The Taylor series of \(z!\) developed at \(z=1/2\), converges for all \(z\) such that \(|z-1/2|<3/2\).

In order to boost the approximation of factorial for real values of the argument, and, especially, for the evaluation for complex values, and the evaluation of the inverse function, the expansions for \(\log(z!)\) and \(1/z!\) are used instead of the direct Taylor expansions above.

Halphing of the imaginary part of the argument

While neither \(z\) nor \((z+1)/2\) is negative integer, the argument of factorial can be dropped with the identity

- \( \mathrm{Factorial}(z)~=~\frac{2^z}{\sqrt{\pi}}~ \mathrm{Factorial}\!\left(\frac{z}{2} \right)\cdot \mathrm{Factorial}\!\left(\frac{z\!-\!1}{2} \right) \)

This may be useful to drop with factor 1/2 the imaginary part of the argument (for example, to apply the Taylor expansion above for the evaluation), but the function has to be evaluated twice.

Related functions

In the plot of factorial of the real argument, the two other functions are plotted, \(\mathrm{ArcFactorial}(x)=\mathrm{factorial}^{-1}(x)\) and \(\mathrm{factorial}(x)^{-1}\). These functions are used for the generalization of the factorial and for its evaluation.

Inverse function

| \(z\) | ArcFactorial\((z)\) |

|---|---|

| \(\mu_0\) | 0.46163214496836234126265954233 |

| \(\frac{\sqrt{\pi}}{2}\) | 0.50000000000000000000000000000 |

| 1 | 1.00000000000000000000000000000 |

| 2 | 2.00000000000000000000000000000 |

| 3 | 2.40586998630956692469992921838 |

| 4 | 2.66403279720644615568638939436 |

| 5 | 2.85235545803172783164299808684 |

| 6 | 3.00000000000000000000000000000 |

Inverse function of factorial can be defined with equation

- \((\mathrm{ArcFactorial}(z))!=z\)

and condition that ArcFactorial is holomorphic in the comlex plane with cut along the part of the real axis, that begins at the minimum value of the factorial of the positive argument, and extends to \(-\infty\). This function is shown with lines of constant real part \(u=\Re(\mathrm{ArcFactorial}(z))\) and lines of constant imaginary part \(v=\Im(\mathrm{ArcFactorial}(z))\).

Levels \(u=1,2,3\) are shown with thick black curves.

Levels \(u=

0.2,\) \(0.4,\) \(0.6,\) \(0.8,\) \(

1.2,\) \(1.4,\) \(1.6,\) \(1.8,\) \(

2.2,\) \(2.4,\) \(2.6,\) \(2.8,

3.2,\) \(3.4,\) \(3.6\) are shown with thin blue curves.

Levels \(v=1,2,3\) are shown with thick blue curves.

Level \(v=0\) is shown with thick pink line.

Levels \(v=-1,-2,-3\) are shown with thick red curves.

The intermediate levels of constant \(v\) are shown with thin dark green curves.

The ArcFactorial has the branch point \(\mu_0 \approx 0.85 \); the cut of the range of holomorphizm is shown with black dashed line.

ArcFactorial for some real values of the argument is approximated in the table at right.

| \(n\) | approximation for \(d_n\) |

|---|---|

| 1 | 1.43764234228440800 |

| 2 | 0.315227181071631549 |

| 3 | -0.0256407066268564423 |

| 4 | 0.00492170392390056555 |

In vicinity of the branchpoint \(z=\mu_0\), the ArcFactorial can be expanded as follows:

- \( \mathrm{ArcFactorial}(z)=\nu_0+\sum_{n=1}^{N-1} d_n\cdot \Big(\log(z/\mu_0) \Big)^{n/2} \)

The approximations for the first coefficients of this expansion are copypasted in the table at right. About of 30 terms in this expansion are sufficient to plot the distribution of the real and the imaginary parts of ArcFactorial in the figure.

Function f(z)=1/z!

The inverse function of factorial, id est, \(\mathrm{ArcFactorial}(z)=\mathrm{Factorial}^{-1}(z)~\) from the previous section, sohuld not be confused with

\(f(z)=\) \(\frac{1}{z!}\) \(

=\mathrm{Factorial}(z)^{-1}\)

\(=\frac{1}{\mathrm{Factorial}(z)}~\),

which is also shown in the figure at right.

The lines of constant \(u=\Re(f(z))\) and

the lines of constant \(v=\Im(f(z))\) are drawn.

The levels \(u=-24,\) \(-20,\) \(-16,\) \(-12,\) \(-8,\) \(-7\) \( .. 7,\) \(8,\) \(12,\) \(16,\) \(20,\) \(24\)

are shown with thick black lines.

The levels \(v=-24,-20,-16,-12,-8,-7 ... 7,-1\) are shown with thick red lines.

The level \(v=0\) is shown with thick pink line.

The levels \(v=1,2, ... 7,8,12,16,20,24\) are shown with thick blue lines.

Some of intermediate elvels \(u=\)const are shown with thin red lines for negative values and thin blue lines for the positive values.

Some of intermediate elvels \(v=\)const are shown with thin green lines.

The blue dashed curves represent the level \(u=1/\mu_0\) and correspond to the positive local maximum of the inverse function of the real argument.

The red dashed curves represent the level \(u=1/\mu_1\), which corresponds to the first negative local maximum of the factorial of the real argument;

\(\mathrm{factorial}^{\prime}(\nu_1)=0\);

\(\mathrm{factorial}(\nu_1)=\mu_1\).

In the upper-left hand side of the figure, and at the lower-left hand side of the figure, the density of levels exceeds the ability of the ploter to draw them, and these parts are left empty.

\(f(z)=\frac{1}{z!}\) is entire function, that grows in the left hand side of the compelx plane and quickly decays to zero along the real axis.

LogFactorial

For the approximation of factorial, it can be expressed as \[ z!=\exp(\mathrm{LogFactorial}(z)) \] At large values of the argument, the LogFactorial does not show the fast growth and is easier for the numerical implementation, than factorial.

At real positive values of the argument, LogFactorial can be interpreted as logarithm of Factorial: \[ \mathrm{LogFactorial}(x)=\ln(\mathrm{LogFactorial}(x)), \ x>0 \]

Function LogFactorial is shown in figure a right with lines of constant real part and lines of constant imaginary part.

Levels of constant \(u=\Re(\mathrm{LogFactorial}(z))\) and

Levels of constant \(v=\Im(\mathrm{LogFactorial}(z))\) are drawn with solid lines:

Levels \(u=-24,\) \(-20,\) \(-16,\) \(-12,\) \(-8,\) \(-7,\) \(-6,\) \(-5,\) \(-4,\) \(-3,\) \(-2,\) \(-1,\) \(0,\) \(1,\) \(2,\) \(3,\) \(4,\) \(5,\) \(6,\) \(7,\) \(8,\) \(12\) \(,16,\) \(20,\) \(24\) are shown with thick black curves.

Levels \(u=\) \(

-3.8,\) \(-3.6,\) \(-3.4,\) \(-3.2\) \(

-2.8,\) \(-2.6,\) \(-2.4,\) \(-2.2\) \(

-1.8,\) \(-1.6,\) \(-1.4,\) \(-1.2\) \(

-0.8,\) \(-0.6,\) \(-0.4,\) \(-0.2\) are shown with thin red curves.

Levels \(u=\) \(

0.2,\) \(0.4,\) \(0.6,\) \(0.8\) \(

1.2,\) \(1.4,\) \(1.6,\) \(1.8\) \(

2.2,\) \(2.4,\) \(1.6,\) \(2.8\) \(

3.2,\) \(3.4,\) \(3.6,\) \(3.8\) are shown with thin blue curves.

Levels \(v=-24,\) \(-20,\) \(-16,\) \(-12,\) \(-8,\) \(-7,\) \(-6,\) \(-5,\) \(-4,\) \(-3,\) \(-2,\) \(-1\) are shown with thick red curves.

Level \(v=0\) is shown with thick pink line.

Levels \(v=1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,12,16,20,24\) are shown with thick blue lines.

Levels \(v=

-3.8,\) \(-3.6,\) \(-3.4,\) \(-3.2\) \(

-2.8,\) \(-2.6,\) \(-2.4,\) \(-2.2\) \(

-1.8,\) \(-1.6,\) \(-1.4,\) \(-1.2\) \(

-0.8,\) \(-0.6,\) \(-0.4,\) \(-0.2\) \(

0.2,\) \(0.4,\) \(0.6,\) \(0.8\) \(

1.2,\) \(1.4,\) \(1.6,\) \(1.8\) \(

2.2,\) \(2.4,\) \(1.6,\) \(2.8\) \(

3.2,\) \(3.4,\) \(3.6,\) \(3.8\) are shown with thin green curves.

The cut of range of holomorphism is shown with black dashed line.

Function LogFactorial has singularities at the same points, as the factorial, id est, at negative integer values of the argument.

| \(n\) | \(a_n\) | approximation of \(a_n\) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 / 12 | 0.083333333333333333 |

| 1 | 1 / 30 | 0.033333333333333333 |

| 2 | 53 / 210 | 0.252380952380952381 |

| 3 | 195 / 371 | 0.525606469002695418 |

Far from the negative part of the real axis, the function LogFactorial can be approximated through the coninual fraction \(p\): \[ \mathrm{LogFactorial}(z)= p(z) + \log(2\pi)/2 - z + (z+1/2)~\log(z) \] \[ p(z)= \frac{a_0}{z+\frac{a_1}{z+\frac{a_2}{z+\frac{a_3}{z+..}}}} \] The coefficients \(a\) and their approximate evaluations are copypasted in the table at right.

In vicinity of the real axis, while the modulus of the imaginary part of LogFactorial does not exceed \(\pi\), the

LogFactorial can be interpreted as lofarithm of factorial, id est,

- \(\mathrm{LogFactorial}(z)=\log(z!)\)

In particular, this relation is valid for positive real values of \(z\).

For all \(z\) except negative integers, \( z!=\exp\!\Big(\mathrm{LogFactorial}(z)\Big)\)

However, the LogFactorial has singularities at negative integer valies of the argument.

Stirling formula

Historically, one of the first approximations of the factorial with elementary functions was the Stirling formula below. For large \(n\) there is an asymptotic approximation due to Scottish mathematician James Stirling \[ n! \approx \sqrt{2\pi} n^{n+1/2} \mathrm e^{-n} \] This formula can be obtained from the approximation for LogFactorial above, just replacing \(p(z)\) to zero.

With more terms, the asymptotic \(A\) can be written as flows: \[ A(z)= \sqrt{2\pi z}\ \exp\left( z\log\frac{z}{\mathrm e} + \frac{1}{12 z} \left( 1 -\frac{1}{30z^2} +\frac{1}{105z^4} -\frac{1}{140z^6} +\frac{1}{99z^8} -\frac{1}{42z^{10}} \right) \right) \]

The figure at right shows the map of agreement

\[

a(z) = - \lg \left(\frac{|z!-A(z)|}{|z!|+|A(z)|}\right).

\]

This agreement estimates, how may significant figures can one expect to get with this approximation.

The map or the agreement \(a\) suggests that the approximation \(A(z)\)

provides of order of 14 decimal digits of Factorial\((z)\) in the range

\[ d = (\ \Re(z) \!\ge\! -6 , \ |z|\!>\!8\ )\ \lor \ (\Re(z)\!<\!-6 , \ |\Im(z)|\!>\!5 \ )

\]

Function \(A\) is interpreted as Restricted asymptotic:

It is the Sectorial asymptotic of Factorial at large values for sector

\[

D= \{ z\in \mathbf C \ : |\arg(z)|< \alpha \}

\]

where \(\alpha\) is any positive real number such that \( \alpha < \pi \).

At large \(|z|\), the residual \(\ r(z)\!=\)Factorial\((z)\!-\!A(z) \ \) remains asymptotically negligible compared to Factorial\((z)\) in the whole complex \(z\) plane except an arbitrarily narrow sector containing the negative real axis: \[ \lim_{|z|\to \infty, \ z \in D} \frac{r(z)}{z!} = 0 \] Here, the limit is not uniform as \(\alpha\to\pi\) . The mathematically precise version of the formula above can be written as follows: \[ \forall \alpha<\pi:\quad \lim_{|z|\to\infty,\ |\arg z|\le \alpha} \frac{r(z)}{z!}=0 \]

In a little bit less efficient form, the asymptotic of Factorial for large values can be written as follows: \[ B(z) = \sqrt{2\pi z} \, \left(\frac{z}{\mathrm e}\right)^z \left(1 +\frac{1}{12z}+\frac{1}{288 z^2} - \frac{139}{51840 z^3} - \frac{571}{2488320 z^4} + \frac{163879}{209018880 z^5} \right) \] Function \(B\) also can be interpreted as Sectorial asymptotic of Factorial, with the same sector \(D\) as for asymptotic \(A\).

Iterated factorial and square root of factorial

Factorial is treated as the Transfer function in book «Superfunctions» [4][5]. This formalism allows to iterate Factorial and, in particular, to evaluate function «Square root of factorial» \(\varphi\) such that \(\varphi(\varphi(x))=x!\).

The iterates of factorial are constructed with the superfunction of factiorial and the inverse function, id est, the SuperFactorial \(F\) and the AbelFactorial \(G=F^{-1}\). The \(n\)th iteration of factorial can be expressed as follows:

\(\mathrm{Factorial}^n(z)= \mathrm{SuperFactorial} \big(n+ \mathrm{AbelFactorial}(z)\big)\)

Where SuperFactorial is superfunction of factorial, id est, solution \(F\) of the transfer equation

\( F(z\!+\!1)= \mathrm{Factorial}(F(z))\)

and \(\mathrm{AbelFactorial}=\mathrm{SuperFactorial}^{-1}\), id est, the inverse function. AbelFactorial is also solution \(G\) of the Abel equation

\(G(z)+1= G(\mathrm{Factorial}(z))\)

The \(n\)th iteration can be calculated also for non-integer values of \(n\), number of iterations can be complex [6].

In particular, at \(n=1/2\), we have \({\rm factorial}^{1/2}(z)=\sqrt{\rm factorial}(z)\), where function \(\sqrt{\,!\,}=\sqrt{\rm factorial}\) can be interpreted as square root of factorial: \(\sqrt{\,!\,}\Big(\sqrt{\,!\,}(z)\Big)=z!\). Name of this function is used as logo of the Physics department of the Moscow State University and part of logo of TORI in 2009-2014, until the beginning of the Russian invasion into Ukraine. (Since 2014, all things related to Russia become toxic; so, the logo had been replaced to formulas for the Square root of exponential.)

Notation \(\sqrt{!} (z)\) happened to be not so convenient. The colleagues, who do not know about Logo of the Physics Department of the Moscow State University, confuse \(~\sqrt{!} (z)=\sqrt{\mathrm{Factorial}}(z)~\) with \(~\sqrt{\mathrm{Factorial}(z)}=\sqrt{z!}~\). For this reason, in TORI, notation \(\mathrm{Factorial}^{1/2}(z)\) is used instead.

Transfer equation

Factorial can be considered as holomorphic solution \(F\) of the generalized transfer equation

\(F(z\!+\!1)= (z\!+\!1) \, F(z)\)

However, \(F=\mathrm{Factorial}\) is not only solution of this equation. Name Hadmard finction is suggested for one of the other solutions [7].

References

- ↑ http://people.math.sfu.ca/~cbm/aands/page_255.htm M.Abramowitz and I.Stegun: Handbook of Mathematical Functions. 6. Gamma Function and Related Functions (2010)

- ↑ Wielandt's theorem online: http://www.math.ku.dk/~henrikp/specialtopic2000/node7.html

- ↑ Reinhold Remmert The American Mathematical Monthly, Vol. 103, No. 3 (Mar., 1996), pp. 214-220, http://www.jstor.org/pss/2975370

- ↑

https://www.amazon.co.jp/-/en/Dmitrii-Kouznetsov/dp/6202672862

https://www.morebooks.de/shop-ui/shop/product/978-620-2-67286-3

https://mizugadro.mydns.jp/BOOK/468.pdf D.Kouznetsov. Superfunctions. Lambert Academic Publishing, 2020. - ↑ https://mizugadro.mydns.jp/BOOK/202.pdf Д.Кузнецов. Суперфункции. Lambert Academic Publishing, 2014.

- ↑ http://www.springerlink.com/content/qt31671237421111/fulltext.pdf?page=1 D.Kouznetsov, H.Trappmann. Superfunctions and square root of factorial. Moscow University Physics Bulletin, 2010, v.65, No.1, p.6-12.

- ↑ http://www.luschny.de/math/factorial/hadamard/HadamardsGammaFunction.html Is the Gamma function mis-defined? Or: Hadamard versus Euler — Who found the better Gamma function? Cited for state for November 2013: The Gamma function of Euler often is thought as the only function which interpolates the factorial numbers n!=1,2,6,24,…// This is far from being true. We will discuss four factorial functions// the Euler factorial function n!,// the Hadamard Gamma function H(n),// the logarithmic single inflected factorial function L(n),// the logarithmic single inflected factorial function L∗(n). ..

http://en.citizendium.org/wiki?title=Factorial

Ronald L. Graham, Donald E. Knuth, Oren Patashnik. Concrete Mathematics. (Addison Wesley, 1989, isbn=0-201-14236-8, pages111,332

https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/superfunktsii-i-koren-iz-faktoriala/viewer

https://mizugadro.mydns.jp/PAPERS/2010superfar.pdf

Кузнецов Д.Ю.Траппманн Г. Суперфункции и корень из факториала.

Вестник Московского Университета, серия 3, 2010 No.1, стр.8-14.

(Текст научной статьи по специальности «Математика»), in Russian

https://www.springerlink.com/content/qt31671237421111/fulltext.pdf?page=1

https://mizugadro.mydns.jp/PAPERS/2010superfae.pdf

D.Kouznetsov, H.Trappmann. Superfunctions and square root of factorial.

Moscow University Physics Bulletin, 2010, v.65, No.1, p.6-12.

Keywords

«Amos», «ArcFactorial», «Arcfactorial», «Arcsuperfac.cin», «Asymptotic», «AuFac.cin», «AuFac», «Binomial coefficient», «Fac.cin», «Facp.cin», «Factorial», «Lof», «LogFactorial», «Restricted asymptotic», «Sectorial asymptotic», «Student Distribution», «Square root of factorial», «SuperFactorial», «Superfactorial», «SuFac.cin», «SuFac»,